Edvard Munch’s Written Language and Handwriting

What type of Norwegian did Edvard Munch write? What was his handwriting like? How did his written language compare to the orthography of his time? Was he influenced by Hans Jæger and the bohemians’ orthophonic way of writing?1 Did the changes in orthography stemming from the language reforms of 1907, 1917 and 1938 make their way into Munch’s written language? And how can we, from our point of reference in a modern written Norwegian language, read his texts without ending up misreading them when his handwriting is so often difficult to read?

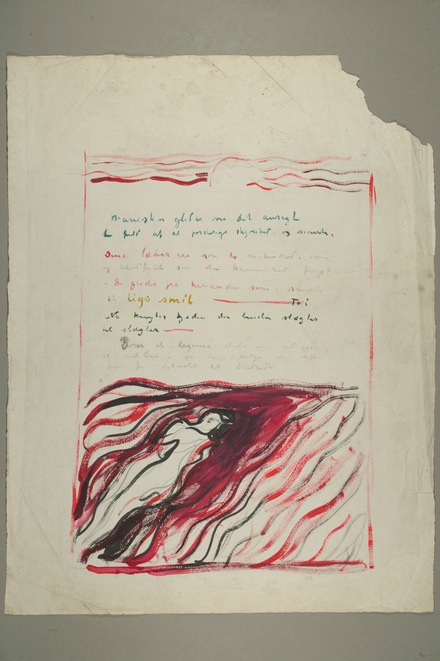

CAT. 59. MOONLIGHT GLIDES ACROSS YOUR FACE ... C 1913

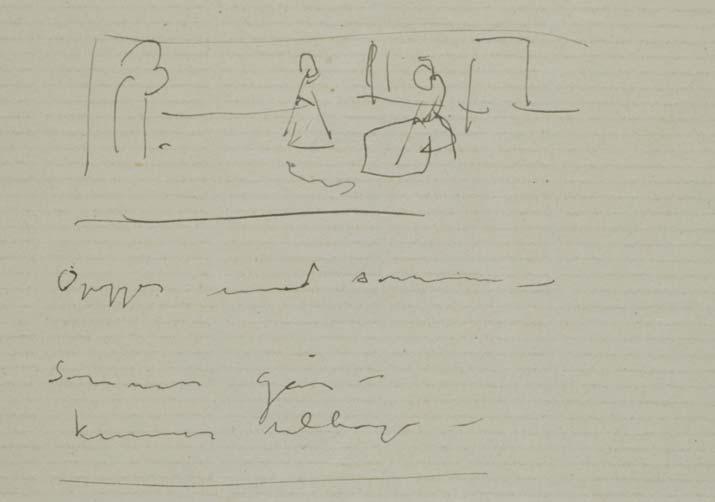

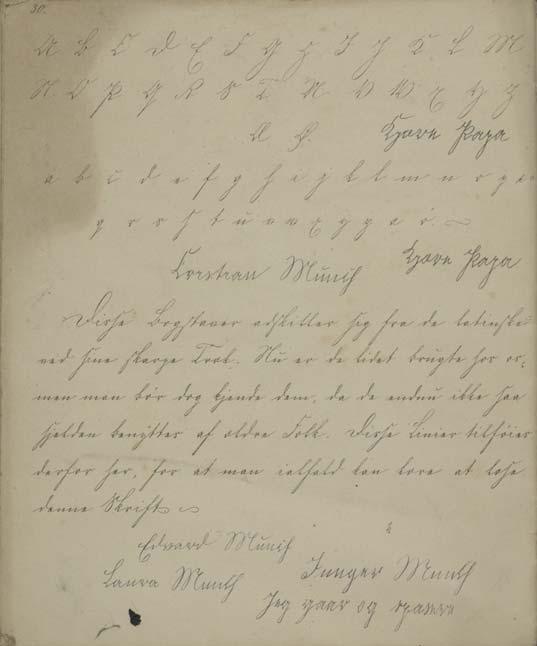

To read handwritten texts is demanding, at times extremely difficult, just as Munch’s handwriting can be. Handwriting distinguishes itself from printed type by being imprecise. Handwriting is affected by historical conditions, individual qualifications and by motivational factors in the writer’s situation. It is affected by the physical and mental circumstances within and around the person writing, by the tools of writing and by the surface that is being written on. Handwriting will thus always be open to a certain degree of interpretation. This means that one will find places in the text where one must choose between several ways of reading, where the text remains uncertain; one will find places in the text where one cannot decipher the word or letter that has been written, which results in holes in the text. This also means that the more the transcriber (one who copies) knows about Munch’s life and work and the better the said person knows the Norwegian written language2 and its historical details and transformations, the fewer the uncertainties and holes in the texts (ill. 2).

In the work of transcribing Munch’s texts, we have set up guidelines3 in order to make sure that the same principles are followed in all of the texts included in the digital archive. A major principle is to read sympathetically. By sympathetic we mean that we take it for granted that what Munch has written or intended to write is or was meant to be meaningful. This is of course not always the case. It is quite possible that there are places in the texts that for some reason were never meaningful. With a sympathetic point of departure one can risk creating a meaningful text out of something that originally was not.

ILL. 2. NOTE, MM N 657-1 (DETAIL)

Munch’s texts consist of about 15 000 pages written in the course of almost 70 years. Now that the digital archive has been launched, it has become possible to analyse his language with greater precision. This article is based on random samplings of a selection of texts,4 and should therefore be considered as a discussion of tendencies in the material.

Handwriting Then and Now

Throughout the centuries handwriting has been a personal tool that allowed humans to store memories, experiences, knowledge and facts by writing them down, and to communicate with one another from afar. Along with the art of printing came the printed type, and since then typewritten type and digital type. Although printed type and digital type dominate today, we still use handwriting to a certain degree, mainly in connection with schooling and studies. For us handwriting is neither the only, nor the most common written form of communication, as it was for Munch and his contemporaries.5 At that time the letter – in all of its variations – was the natural means of making contact and maintaining contact with other persons. During the second half of Munch’s life, the telephone came into common use but he evidently preferred the letter to the telephone, a form of communication it seems he never quite became accustomed to.6

The Character of the Written Language

The written language that Munch learned to write was almost identical with the Danish written language. In the course of his lifetime the written language underwent extensive orthographic reforms (1907, 1917 and 1938), whose tendencies were to adapt the written language in the direction of vernacular forms.7

For the reader of today Munch’s written language seems old-fashioned in his early as well as later texts. Here are a few examples of writing which we perceive as antiquated and which Munch uses throughout his life; ‘Billeder’ (today bilder) [pictures], ‘bliver’ and ‘blevet’ (but he also writes the more modern ‘blir’ and ‘blit’) [becomes and became], ‘blot’ (bare) [only], ‘gnaver’ (gnager) [gnaws], ‘Nervernes Bølgeluner’ [the capricious fluctuations of the nerves], ‘tak’ (takk) [thank-you], ‘undgjælde’ (unngjelde) [suffer/ pay for], ‘ven’ (venn) [friend], ‘det skulde været mig’ (det skulle vært meg) [it should have been me], ‘jeg har havt så meget at fare med’ (jeg har hatt så mye å gjøre) [I have had so much to do/been so busy]. In 1943 Munch still uses forms such as ‘lige’ (like) [like/similar], ‘mit’ (mitt) [my/mine], ‘tat’ (tatt) [taken], ‘dage’ (dager) [days], ‘besøg’ (besøk) [visit, n.], ‘kjøbt’ (kjøpt) [bought], ‘op’ (opp) [up], ‘af’ (av) [of, off], ‘at hjælpe’ (å hjelpe) [to help], ‘voxne’ (voksne) [adults] and ‘frugttræer’ (frukttrær) [fruit trees]. Munch did not replace b, d and g with p, t and k, which was introduced in Norwegian with the written language reform of 1907. Neither did he replace æ with e (læse – lese) [to read], which was introduced with the language reform of 1917. The same reform changes of ld/nd to ll/nn (fjeld – fjell, mand – mann) [mountain – man/husband] can occasionally be seen in Munch’s written language style, but it is not consistent. Munch often alternates between various forms of the same word in one and the same text.

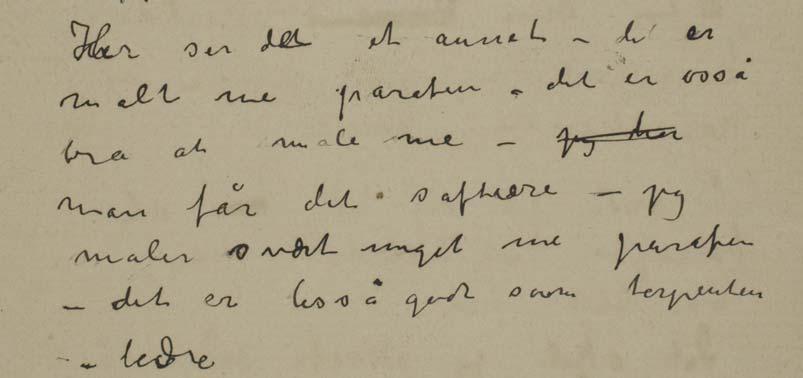

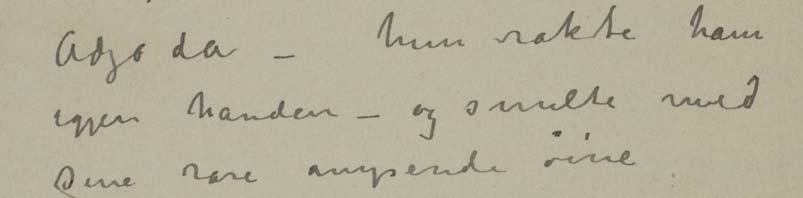

ILL. 3. NOTE, MM N 102-1 (DETAIL)

If we take a closer look, however, it is also possible to see modern and/or more Norwegian tendencies [as opposed to Danish, trans.note] in Munch’s written language. He used Norwegian forms such as ‘reise’ (Da. rejse) [to travel], ‘øie’ (Da. øje) though not the more modern øye [eye], ‘vei’ (Da. vej) [road, way] and ‘kjøre’ (Da. køre) [to drive]. Munch began early on to use å in place of aa, though not to indicate the infinitive. For the most part he used at to indicate the infinitive his whole life, for example ‘at hjælpe’ [to help]. The transition from aa to å occurred formally in Norwegian with the language reform of 1917. By that time å had already been in general use. Munch learned to write aa, as one can see in his early texts, but he started to write å in the early 1880s.8 The form aa instead of å does nevertheless occasionally appear in Munch’s later texts.

Bohemian and Orthophonic Usage

It is commonly believed that Munch was inspired by Hans Jæger and the Kristiania circle of bohemian writers and artists. One of their well-known tenants was: “Thou shalt write thine own life”.9 It is likely that Munch was influenced by this idea. The subject matter of many of his notes and literary sketches is based on episodes from his life, whether or not he uses a first person or third person narrator, or real or fictive names. One can thus claim that he followed the dictate of the bohemians to write his own life. But did Munch also follow Jæger’s leaning towards a more vernacular, orthophonic style of writing? Jæger went very far in adapting his written style to the way the words were enunciated. If we look at the orthophonic features of Munch’s written language, we can compare them with Jæger’s style of writing.

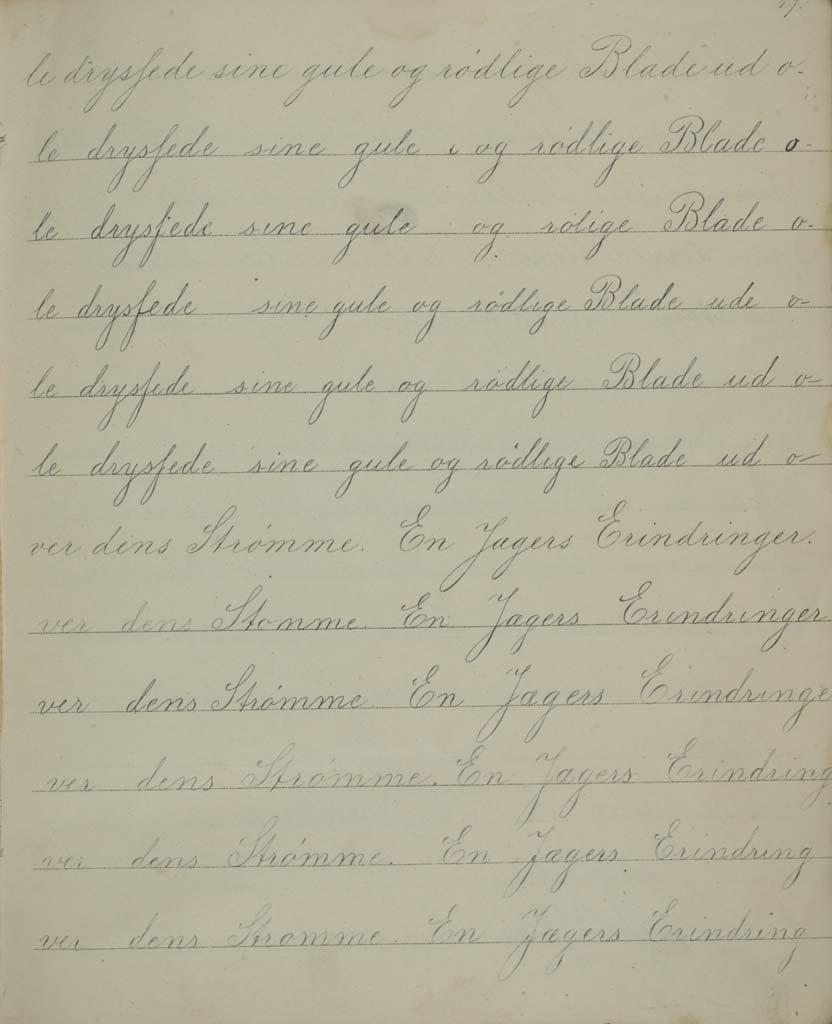

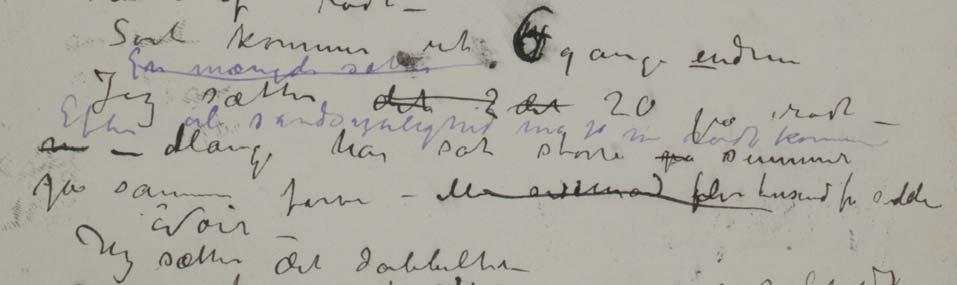

ILL. 4. PAGE FROM A SCHOOL BOOK SHOWING EDVARD MUNCH’S EXERCISES IN PENMANSHIP, BASED ON A PRINTED PATTERN, MM T 2809-17

In Syk Kjærlihet10 [Sick Love] Jæger writes ‘jei’, ‘mei’, ‘halt’, ‘uhyggeli’, ‘maaren’, ‘hulle’, ‘holler’, ‘lissaa’, ‘me’, ‘a’ instead of jeg [I], mig [me], halvt [half], uhyggelig [sinister/horrifying], morgen [morning], hullet [hole], holder [holds/grasps], likeså [likewise/equally], med [with], af [of/off]. In other words, he leaves out or replaces letters that are not pronounced. This is not used consistently in all words, for instance in proper names (‘Bjørck’) or foreign words (‘jaloux’ for sjalu [jealous]), but is done often enough to give the written style an oral character.

Munch did not write jei etc., but he gradually acquired writing habits that tended toward an orthophonic usage even though he did not adopt the many orthophonic changes in spelling that the reforms of 1907, 1917 and 1938 introduced (cf. “The Character of the Written Language” above). Munch’s orthophonic tendencies are thus closer to Jæger’s style of writing than the official written standard. In words where the g is not pronounced, as in også [also] and rolig [calm/quiet], Munch omitted the g and wrote ‘osså’ and ‘roli’. The changes appear sporadically beginning in 1889, cf. for instance MM N 33, where he wrote ‘krafti’ [powerful/ energetic/potent] and ‘færdi’ [finished] in one text, to then write ‘kraftig’ and ‘færdig’ in the next version of the text; or MM N 120, which is dated March 1890, where he wrote ‘osså’ in one text and ‘også’ in another. Munch retained this type of inconsistent spelling usage for the rest of his life (ill. 3).

ILL. 5. PAGE FROM ONE OF EDVARD MUNCH’S SCHOOL BOOKS SHOWING THE GOTHIC ALPHABET AND HANDWRITING, MM T 2809-30

When Munch wrote in French he sometimes made mistakes that were similar to the omission of g in ‘krafti’. He omitted the silent plural ending, for example. He wrote ‘des salutation’ instead of des salutations (MM N 3406) and ‘mes tableaux donne’ instead of mes tableaux donnent (MM N 3405).11 In other words, Munch sometimes omitted silent letters in favour of an orthophonic spelling, yet he was not consistent in French either – he could suddenly use the correct spelling. Whether the vacillation was due to a poor knowledge of French or to orthophonic French, is difficult to say. One can find a similar case in Munch’s German. He consistently wrote -ich instead of -ig as the suffix in certain words: ‘richtich’, ‘wichtich’, ‘würdich’, ‘liebenswürdich’ instead of richtig, wichtig, würdig, liebenswürdig.12 It is an orthophonic mistake (given the northern German pronunciation of the words), but whether the mistake is deliberate or not is difficult to determine.

The Character of the Handwriting13

Munch’s handwriting as a young man is neat and attractive, and one can see that he has done writing exercises and learned penmanship. The writing is legible and comprehensible.

At a very young age Munch wrote nouns with upper-case letters: ‘Eventyrbøger’, ‘Regning’, ‘Kjoletøi’, ‘Melk’, ‘Kage’ and ‘Tordenvær’ [Fairytale Books, Arithmetic/ Bill/Receipt, Dress Material, Milk, Cake and Thunder]. He stopped this habit in his youth, and later mainly wrote nouns with lower-case letters.

ILL. 6. NOTE, MM N 494-1 (DETAIL)

Like all of his contemporaries, Munch learned the Latin alphabet, but in his Norwegian texts a gothic s appears sporadically. Some of his schoolbooks have been preserved, and among them are some that contain lessons in penmanship, cf. for example MM T 2809. In this book Munch learned to use the Gothic s as one of the s’es in the double s, a spelling that was common in written Norwegian then (ill. 4). The book also reveals that the students were taught the Gothic alphabet so that they could read and understand it, as it was still common among older people to write in the Gothic alphabet. Munch, who read and wrote German, of course used the Gothic s there as well (ill. 5).

The adult Munch, on the other hand, is not particularly meticulous with either penmanship or punctuation. When he writes letters, he often omits diacritical marks, for instance, the a-circle (å), the tilde mark over u (ū), y (ȳ) og o (ō), or the dot over i. A missing circle over the å can be distracting when attempting to read Munch’s handwritten texts, but it rarely causes problems in comprehension since it is usually easy to determine which mark is missing or which word he intended to write based on the context (ill. 6).

This applies as well to o instead of ø; it is very rare that misinterpretations occur. It was also common to mark u and y with a tilde accent in order to differentiate them from other letters, but here the omission does not cause a difference in meaning, nor does it have much to say for our understanding or reading, since the tilde accent is no longer in use and we are therefore used to reading the letters without it.

The lack of a dot over an i, on the other hand, can cause problems since the letter without the dot is formed in the same way as e and can thus be confused with e. Add to this the fact that e instead of i can in some cases lead to a new meaningful word (for example dit hus contra det hus) [your house contra that house], though not always a word that is meaningful in the context. Or it leads to modern versions of the same word, as in the case of dig, mig, sig which become deg, meg, seg [you, me, oneself], which Munch wrote as dig, mig and sig when he was young, and most likely as an adult and old man as well. Dig, mig and sig were replaced with deg, meg and seg with the orthographic reform of 1938. In the digital archive eMunch.no the words are transcribed as dig, mig and sig, providing it is not obvious that he had written an e. In the cases where both i and e create a meaningful word, we have used our knowledge of Munch’s writing habits, the history of written Norwegian and informed judgement to determine whether the word should be written with an i or an e.

ILL. 7. NOTE, MM N 1-4 (DETAIL)

As with the diacritical marks, one occasionally runs into problems determining whether an upper-case or a lower-case letter is used in proper names or in polite forms of address. It was not uncommon to have several variants for writing an upper-case or lower-case letter. A and d in particular seem to vary quite a lot. To complicate matters even more regarding the polite form of address, at one time it was not unusual to write De and Dem [you and thee] with small letters.

In Munch’s case changes and rewriting were done hastily and while in the act of writing. When he from time to time made changes while re-reading the text at a later date, it is most often revealed by the colour, quality, etc. of the writing (ill. 7).

There is often a difference in the quality of the writing between notes, literary drafts and drafts of letters on the one hand, and posted letters on the other. There is also a difference between texts of varying character and having varying content. When something excited him or in some other way demanded tempo, the writing is more rushed and difficult to read.

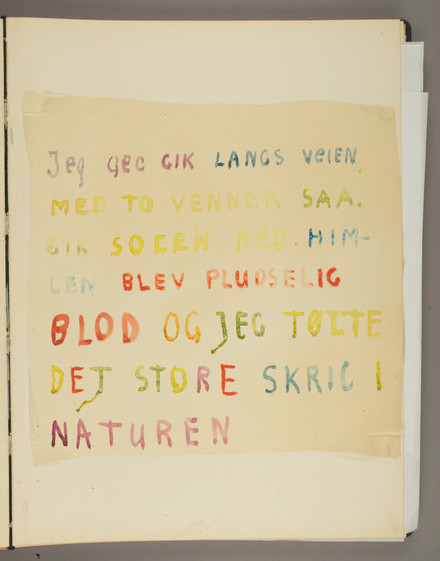

CAT. 67. THE SCREAM TEXT 1930–35

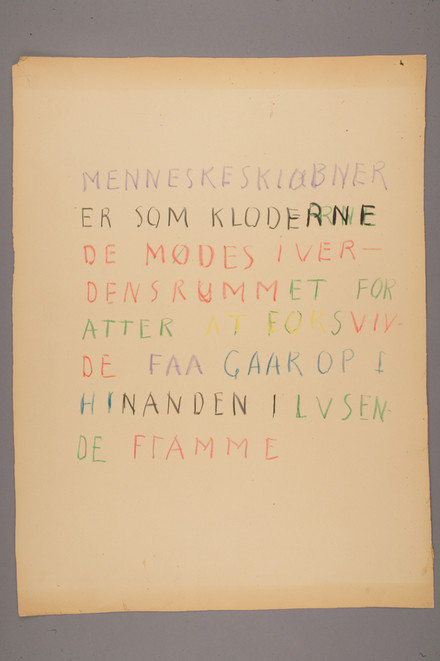

CAT. 66. HUMAN DESTINIES ... 1930–35

Writing Habits

Munch’s penmanship is often sloppy. The combination of his peculiar penmanship and tendency to write orthophonically, his light-handed way of forming the letters, together with the changes in the ways the letters are written (Gothic s, vowels without diacritical marks), means that many of the words are difficult to read and transcribe. Listed below are examples of what we consider to be Munch’s writing habits and what we define as errors in writing.

- Writing habits that are systematic

- Combinations of the letters e and r, n, m create a continuous wavy line in which none of the letters are individuated. Typical for Munch are words with the plural suffixes ‘...erne’, ‘...ener’

- The i cannot be seen in ‘til’ [to/for] and often not in the adjectival/adverbial suffix ‘...lig’ and ‘...dig’ either

- An e at the end of a word can often just appear as the ending of the preceding letter, for example as a long drawn-out k-stroke

- The final r when conjugating a verb in the present tense, for example (skriver, hopper, danser etc. [writes, jumps, dances, etc.]), often resembles an s

- An extra ‘wave’ on a u when it is the first letter in a word (for example in ‘udviklende’ [stimulating/broadening])

- Errors in writing that are coincidental

- The lack of a consonant in a word having double consonants, for example ‘eler’ for eller [or]

- Words that lack one or more letters in the middle, ‘tidigere’ for tidligere [previously, once] ‘landhander’ for landhandler [general store owner]

- Wrong letter, ‘bekynte’ for begynte [began]

- Reversed letters, ’gange’ [gait] for gagne [benefit/profit]

The manner of writing that is considered to be the result of Munch’s writing habits are standardised in eMunch.no to conform to correct writing (we transcribe til [to] even though he writes ‘tl’), but cases that we consider to be errors in writing, are allowed to remain as they are written by Munch. As an example one can see on a page of The Tree of Knowledge (cat. 67) how Munch has written a version of the Scream text. Here it reads “Jeg gec GIK” [I welked walked], with the meaningless “gec” [welked] not crossed out, and further down the page: “JEG TØLTE DET STORE SKRIC” [I telt a great screan] instead of jeg følte det store skrig [I felt a great scream...]. Several of the letters are indistinct, yet Munch has not corrected the text but left it as we can read it today.

Punctuation

One of the most visible characteristics of Munch’s writing is his careless punctuation. You find it in fact in all of his texts whether he wrote in Norwegian, German, French or (only sporadically) English.

At an early age he essentially follows the rules of punctuation in the same way that he follows the rules of orthography. But the punctuation soon changes dramatically, and the comma, period, exclamation point and question mark are used less and less frequently. At times hardly any punctuation marks are used beyond a dash and sporadically also an extra long space between words. The interval spaces indicate a pause between two sentences. A capital letter in the beginning of a new sentence can be missing, and it is not rare, therefore, to find sentences without a final punctuation mark followed by a new sentence that is introduced with a lower-case letter. This makes a reading of the text difficult.

Munch’s Education

Erik Mørstad, in his article “Edvard Munch’s First School Years: Teachers and Textbooks on Drawing”,14 estimates that Munch had approximately one year of public schooling before, at the age of 15, he began studying at the Kristiania Technical College in 1879. Here, as in his later education, he was soon exempted from all instruction with the exception of drawing. Munch had also received tutoring at home in his childhood, mainly because he was often ill for long periods while growing up. However, it is difficult to know precisely how much instruction he actually received at home.

According to Mørstad it was unusual for Norwegian children of school age to receive as little schooling as Munch did. One should keep this fact in mind when observing his written language and handwriting. His written language at a young age is good, and it adheres to the rules of orthography and punctuation of the time. Why he changed his style of writing as a young adult and wrote an inconsistently spelled written language almost without punctuation for the rest of his life is difficult to say. It could be that Munch was not consciously aware of this change, because he does not write anywhere about his written language. The reason for the change in his writing can be carelessness, or a focus on the content and an indifference towards orthography. Regardless, it remains a fact that he originally knew better.

Conclusion

Handwriting has been (and is) a highly personal, and yes, often private tool for humans. One can see this when studying Munch’s papers. He had a way of writing that was marked by his personality, a handwriting with peculiar writing habits and a temperament that affected his handwriting. The outcome of this is that his texts are often difficult to read. The historical distance between Munch and us can also lead to difficulties in reading him. We are dependent on knowledge about Munch’s life, the development of written Norwegian and the practice of penmanship during the 19th and 20th centuries to aid us in our reading.

Notes

1 That is to say an audible style of writing, “as one enunciates the word”.

2 This of course also applies to the other written languages that Munch employs.

3 A complete overview of the transcription guidelines is found in the digital archive of Munch’s texts.

4 In chronological order: MM N 716, MM N 717, PN 303, PN 195, MM N 33, MM N 63, MM N 120, MM N 3035, MM N 3037, MM N 3664, PN 774, MM N 490, PN 264, MM N 3679, MM N 2866, PN 711, MM N 687, MM N 1655, MM N 1677, MM N 2173, MM N 679, MM N 1617, MM N 526, MM N 1683, MM N 405, MM N 1162, MM N 561, MM N 2955, MM N 2962, MM N 3018, MM N 3020, MM N 3307, PN 326, MM N 3492, all in the Munch Museum (MM no.) and the National Library of Norway (PN no.).

5 There are also texts written on a typewriter among Munch’s texts, but these are not included in this discussion.

6 He sometimes comments on this in letters, cf. for example the draft of a letter to an unknown person, MM N 405 (Munch Museum): “What I believe is a comfort and joy for many is that I will no longer use the telephone for any other purpose than for telegrams. It is pure nonsense and one should pity the brave souls who are often dizzy while on the telephone –”.

7 For details cf. the article “Bokmålsrettskrivningen i vårt århundre” by Ståle Løland (The article is taken from Språknytt 1/1997), http://www.sprakrad.no/Politikk-Fakta/Fakta/ Rettskrivingsreformer/Bokmalsrettskrivningen-pa-1900-tallet/. Cf. also the sections entitled “Knud Knudsen og bokmålet” and “Tilnærmingspolitikk” in the article “Fakta om norsk språk”, http://www.sprakrad.no/Politikk-Fakta/Fakta/.

8 Cf. for example MM T 2845 (Munch Museum), dated 1880, and NB Brevsaml. [National Library of Norway, Collection of letters] 518, dated 14.12.1884 (PN 303).

9 Cf. the articles by Hilde Dybvik and Sivert Thue in the printed catalogue.

10 The first volume of Hans Jæger’s trilogy about the Kristiania bohemians. Syk Kjærlihet, Pax Forlag AS, Oslo 1989. The examples are only a small selection of words with divergent orthography.

11 Cf. Henninge M. Solberg’s article.

12 My thanks to Sibylle Söring for this bit of information. Cf. Christian Janss’s article.

13 Rolf E. Stenersen wrote about Munch’s handwriting in his book Edvard Munch : Nærbilde av et geni/Edvard Munch : Close-Up of A Genius (First English edition, Oslo 1969).

14 In the exhibition catalogue Munch Becoming “Munch”. Artistic Strategies 1880–1892, Munch Museum 2008.

Translated from Norwegian by Francesca M. Nichols