Edvard Munch and the French Language

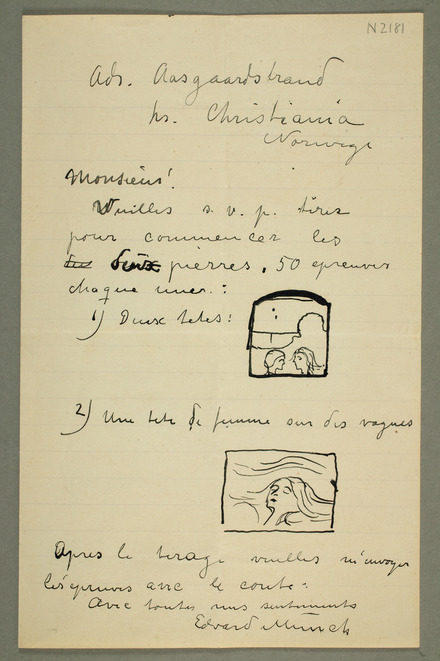

ILL. 9. DRAFT OF A LETTER, EDVARD MUNCH TO THE FRENCH LITHOGRAPHER AUGUSTE CLOT, C 1896–97, MM N 2181-1

“I have difficulties writing, and especially in French”, writes Edvard Munch in an undated draft of a letter. This is by no means an exaggeration. To have a go at Munch’s French texts is a demanding task – one must have patience as well as imagination in order to read and understand them. Munch’s careless and hard to decipher handwriting is one reason for this, but it is mainly owing to the fact that he rarely respects the numerous rules of written French. From the start, we can speak of attempting to decipher, rather than to read the texts. But as one begins to make sense of them, one can glimpse a kind of logic behind Munch’s solutions, and spot a few clues that one can rely upon while reading.

Munch lived and studied in France during several periods, the first being in 1885 when he was 22 years old. Throughout his life he gained many contacts in France and he thus found it necessary to write letters in French. It is therefore natural that most of the French texts that he left behind are drafts of business letters, and the examples in this article are taken from these rough copies. Beyond that, the material consists of notes and other shorter texts.

CAT. 3. KAREN BJØLSTAD IN THE ROCKING CHAIR 1883

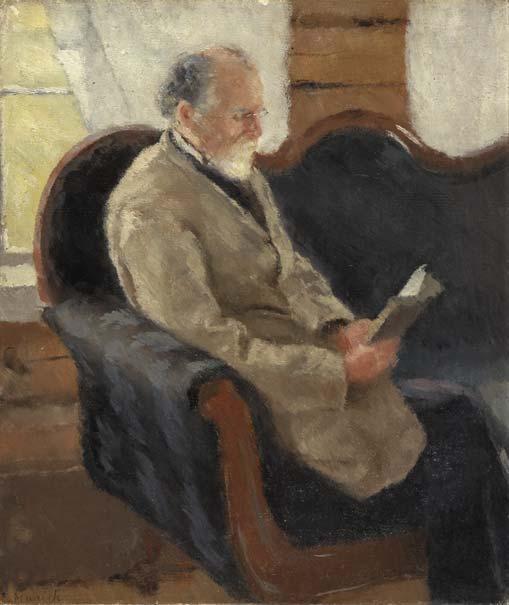

CAT. 2. CHRISTIAN MUNCH ON THE COUCH 1883

Characteristic Features of Munch’s French

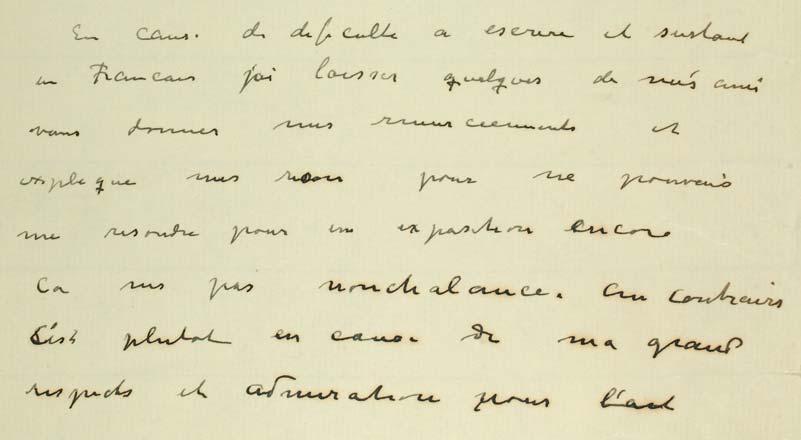

We can read in Munch’s journals that he was given some instruction in French while young. He must have learned something of the language while living in France as well, but we know little about how he mastered the language verbally. As we shall see, there is reason to believe that he spoke French somewhat better than he wrote it. But let us first examine a typical French sentence from Munch’s hand. The passage where he maintains that he has difficulty writing in French, which is found in the letter draft MM N 3407 (ill. 10), can serve as an example as well as any other: “En cause de dificulte a escrire et surtout en Francais j’ai laisser quelques de més ami vous donner mes remerciements [...]”. With a bit of goodwill this can be translated as follows: “Because I have difficulty writing, and especially in French, I have allowed some friends of mine to thank You on my behalf [ ...]”. We find the following characteristic mistakes here:

- The misspelling of silent letters

Munch omits, misspells or adds sounds that are not pronounced. In this sentence, for example, he writes “laisser” for “laissé” and “ami” for “amis”. - Lack of congruence

There is rarely an agreement in gender and number in Munch’s French sentences. The mistakes appear between all classes of words that require agreement when being declined. In this case, for example, he uses “més” [mes], which is plural, in relation to “ami”, which is singular – the equivalent of “mine venn” in Norwegian. [In English this would not be a problem since the possessive pronoun “my” is used for both singular “friend”, and plural “friends”.] - Lack of, or misplaced, diacritic marks

Munch omits or misplaces accent marks and the cedilla, for example: He writes “dificulte” for “difficulté”, “a” for “à”, “Francais” for “français” and “més” for “mes”. - Incorrect form of the word or incorrect expression

Words and expressions which for different reasons are not quite correct appear frequently. Here illustrated by “En cause de”, instead of “À cause de”, and “escrire”, instead of “écrire”. - Other types of spelling mistakes

In addition to the above-mentioned points are various minor spelling mistakes. In this sentence, for example, he writes a single consonant where there should be a double consonant (“dificulte” instead of “difficulté”) and uses an upper-case letter where there should be a lower-case letter (“Francais” instead of “français”).

Although the mistakes appear so often that they continuously interrupt the reading – in this short sentence there are at least 10 large or small mistakes – with a little imagination it is almost always possible to understand what Munch wishes to say, albeit more or less roughly speaking. What is common for several of the points above is that even though the written presentation of the word is incorrect, a reading out loud would produce the correct word. As with Munch’s Norwegian texts1 there is a tendency towards orthophonic usage in the French texts.

Orthophonic Usage in Munch’s French

A sentence in the letter draft MN N 2181 can serve as an example of this and demonstrates how Munch’s spelling mistakes occasionally cause some sentences to become ambiguous or involuntarily comical. In this text he asks the addressee to print and send him 100 prints. He writes: “Apres le tirage veuilles m’envoyer les’ epreuves avec le conte” – he asks to have the prints sent to him together with “le conte”. “Conte” means story, which is meaningless in this connection. But based on the context, we can assume that he means “compte”, that is, the bill – since these two words are pronounced in the same way in French.

ILL. 10. DRAFT OF A LETTER, EDVARD MUNCH TO ANDRÉ DEZARROIS, DIRECTOR OF THE GALERIE NATIONALE DU JEU DE PAUME, PARIS 1939, MM N 3407-1

What this mistake illustrates is that Munch spells in a way that makes it useful for the reader to concentrate on how the words are pronounced, and to try to overlook how Munch reproduces them in writing. Munch’s French often appears as a transcription of what he has heard, and many of the misspelled words are pronounced nearly correctly. One of the most characteristic mistakes he makes is precisely that he misspells silent letters, which the French language has an abundance of. In addition to the examples above are the following typical cases: “pris” for “prix” (price, cost) (for example MM N 3398-1, MM N 3405-1), “ches” for “chez” (at the home of) (for example MM N 3398-1, MM N 3401-2) and “recever” for “recevez” (receive, accept) (MM N 3398-2). A related mistake is that he mixes letters that can be pronounced more or less similarly, such as c and s. One can thus say that there is a tendency towards orthophonic usage in Munch’s French texts – that is, a reproduction of how the words are enunciated – even though it is in no way consistent or found throughout.

Based on the fact that Munch makes many other mistakes as well, it is reasonable to believe that the orthophonic features are not the result of a wish to follow a specific language ideology, but rather of poor knowledge of French. This tendency might indicate that Munch’s spoken French was somewhat better than his written mastery of the language. That he has a relatively varied and precise vocabulary points in the same direction.

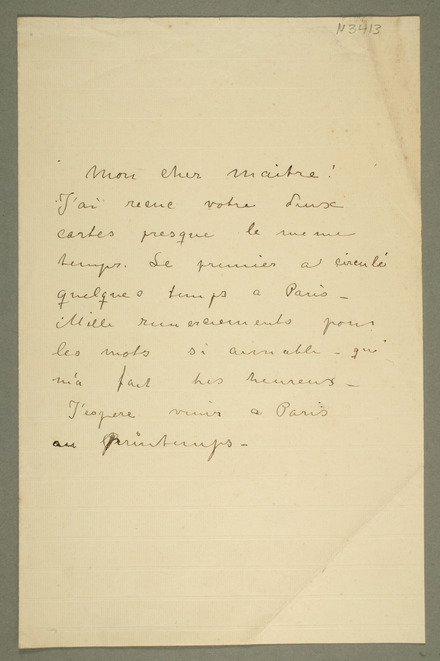

ILL. 11. DRAFT OF A LETTER, EDVARD MUNCH TO THE FRENCH POET STÉPHANE MALLARMÉ 1897, MM N 3413-1

Munch’s Handwriting

The example from the letter draft MM N 2181 demonstrates how Munch’s careless handwriting further complicates a reading of the texts, in the sense that it makes it difficult to determine once and for all what has been written. The word “conte” can also be read as “coute”, a misspelling of “coût”; that is, price, cost. He most likely meant “compte”, but we cannot be completely certain. This uncertainty exists throughout the texts, whether in the case of words, as here, or of letters – one is constantly in doubt as to whether an expected letter is actually there, whether it is lacking, or whether a different letter exists in its place. Yet even though the texts are not always completely clear, it is possible for the most part to understand the gist of Munch’s message. In MM N 2181 there is no doubt that he wishes to have a specific job done and then to have the bill sent to him.

Influences from Other Languages

There are many examples of a possible influence from Norwegian in the French material; that is to say, the transfer of Norwegian modes of expression or language practices to the French language. A repeated example can be found in the sentences where Munch thanks the recipient of the letter. In Norwegian we say “takk” (“thanks”, “thank you”) og “å takke” (“to thank”), where the French use “merci” and “remercier”. The verb has a prefix in French (re-), but not in Norwegian, and Munch omits this prefix in many cases: He writes “je vous merci” where it should have said “je vous remercie” (“I thank You”). Though Munch does use “remercie” in some of the letters. This can be an indication that some of the mistakes are due to carelessness, and not to a lack of knowledge about the language, or perhaps that he had at some point learned the correct expression.

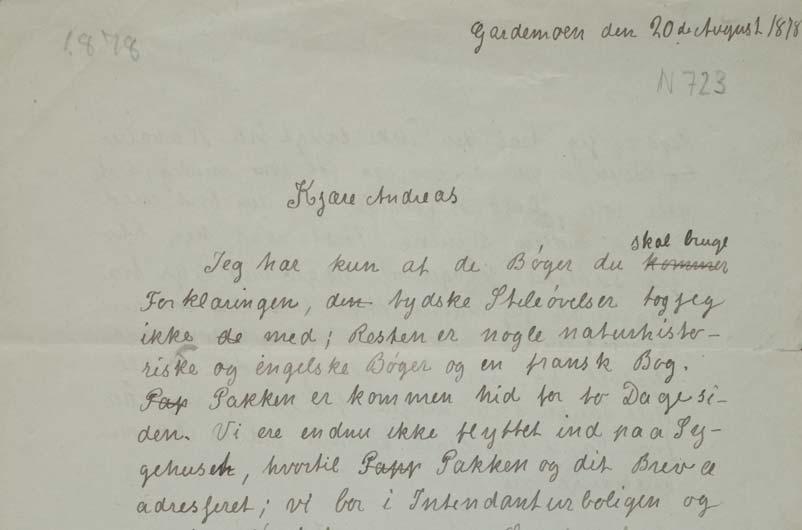

ILL. 12. LETTER FROM EDVARD MUNCH TO HIS BROTHER ANDREAS MUNCH 1878, MM N 723 (DETAIL)

Another example of possible influence from Norwegian can be found in MM N 3412-1, where he writes: “mon dieu comme les jours se chance”. The sentence does not actually make any sense, but if we assume that by “chance” he means “changent”; that is, “change”, which is feasible based on the context, it appears that he wishes to say; “Lord, how the days are changing”. In French the verb should not be reflexive here, as it should be in Norwegian – so the use of “se” is incorrect. Munch thus uses the Norwegian construction in French as well.

Other examples are the cases where he writes “Nowember” for “novembre” and “Juni” for “juin” (MM N 3406-3), which also demonstrates how he allows the Norwegian language to influence the French.

On the other hand, these examples occur only sporadically. One would think that the syntax would be influenced by Norwegian more often, but there are only a few instances of this. Actually, the syntax seems to be more influenced by German. The sentences “Je n’a pas pense les tableaux vendre” (MM N 3405-1) and “Pour mon art comprendre” (MM N 3405-2) are examples of this. A direct translation of these sentences would read: “I have not thought of the paintings to sell” and “In order my art to understand”. Munch places the verb at the end of the sentence, as one would have done in German, but in both Norwegian and French it would be placed earlier in the sentence. It is not so easy to pinpoint a reason for this possible German influence, but it is perhaps not so unnatural that Munch allowed the customs and rules of the foreign languages that he wrote, to overlap one another.

Pragmatic French

Munch does not pay much attention to the rules of language in the French texts he has left behind. He is inconsistent, and therefore the train of thought often seems indecisive and unclear. Because of this, it is easy to get the impression that the texts were penned by a distracted, careless and impulsive correspondent. But the more one reads Munch’s correspondence in French, the more clearly the image appears of a letter writer who has expediency in mind, who first and foremost views the letters purely as a means of communication. Despite the many mistakes, the necessary information is conveyed almost without exception, and that must also have been the most important factor for the businessman Munch. He has learned as much of the French language as he needs to for his purposes, and he is familiar with the required terminology. The texts are therefore most of all proof of a pragmatic approach on Munch’s part – and not least of his courage to have a go at something he does not totally master.

Notes

1 Cf. Hilde Bøe’s article in the present catalogue.

Translated from Norwegian by Francesca M. Nichols